The Turkish president Erdogan’s recent decision to change Hagia Sophia from a museum back into a mosque is significant. The political implications are discussed by experts elsewhere. Here, let’s take a look at the remarkable museum that Hagia Sophia was and, if all goes well, may unofficially remain. What is so significant about this place that it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is consistently one of Turkey’s most-visited attractions? What about the building makes it a museum, and what are its exhibits?

Byzantine Phase

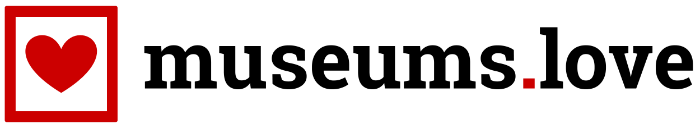

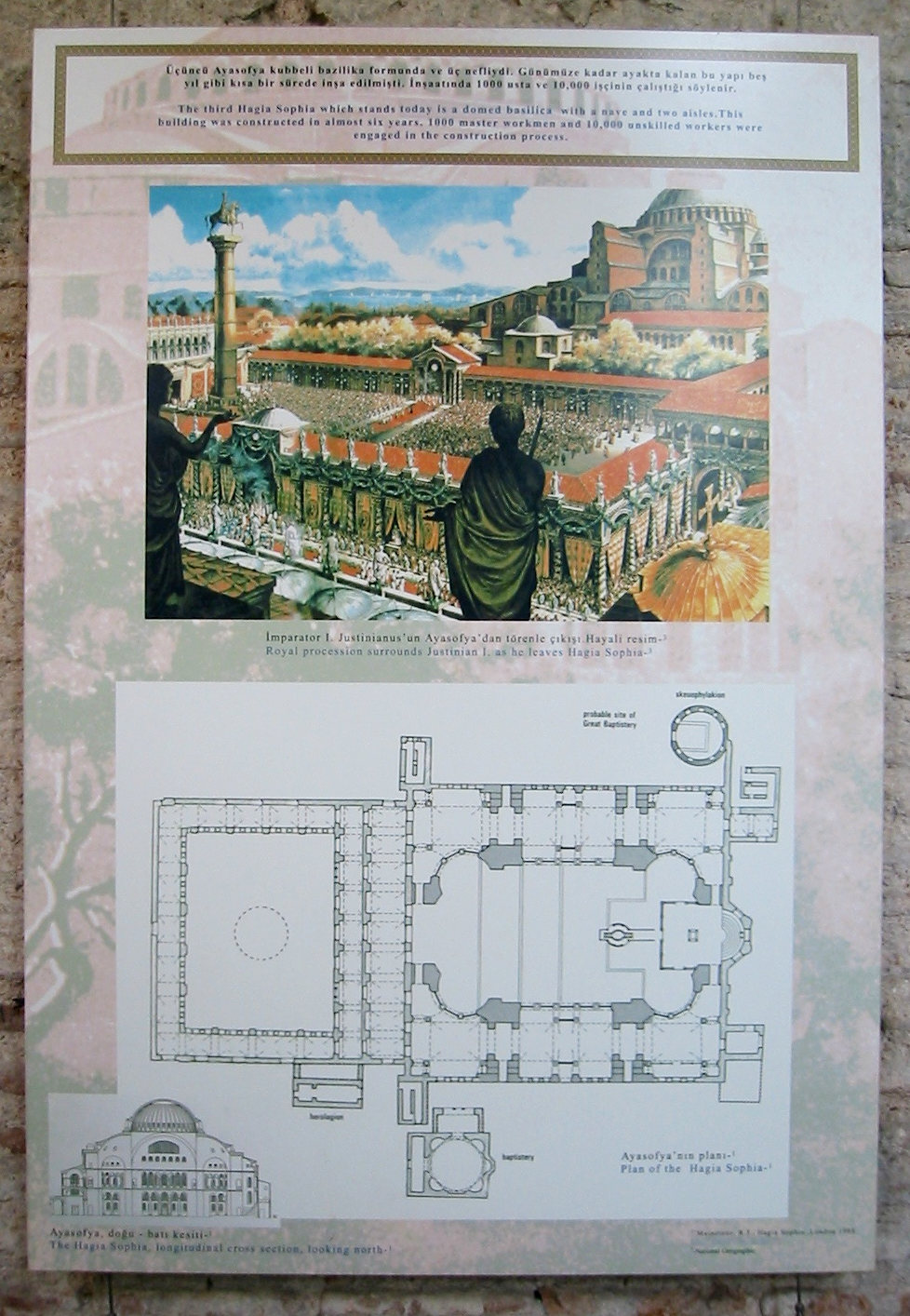

Architecturally, Hagia Sophia is a pioneer. Its use of vaults was unprecedented when it was built in the mid-6th century AD, back when Istanbul was the Byzantine capital city Constantinople. The huge central dome balances atop a cascade of smaller domes and vaults, which support its huge weight. It was the biggest dome in the world for over 1000 years! (Surpassed only by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in the Renaissance.) In this stage of Hagia Sophia’s long life, the building served as a church – and an expression of power for Justianian, the emperor who commissioned it.

Although Istanbul’s cityscape certainly looked different in the 6th c. AD than it does now, it was every bit as cosmopolitan and urbanized. Some signs in Hagia Sophia, although scarce and old, give an impression of this. It will be interesting to see whether such signage will find a place in Hagia Sophia after it is no longer officially a museum.

Artistically too, the Byzantine building is a treasure. The marble capitals on the columns are carved in an intricate “basketweave” form, and the gilded mosaics on the walls and ceilings are breathtaking. Marble panels on the walls display the “butterfly” or “bookmatching” technique, in which two panels cut adjacently from the same block are opened outward from their common surface (like opening a book) and attached to the wall side-by-side to show off their symmetrical pattern.

In the center of the main dome is a mosaic depicting Mary holding the baby Jesus. They are surrounded by a gold surface that highlights their divinity. Both the divinity of Mary and her pose here as the bearer of God, or theotokos, reflect important developments in the early Christian church and iconography at the time. Mary was acknowledged as theotokos at one of the numerous church councils held in this period. Tragically, every single one of Hagia Sophia’s original 6th-century figural mosaics were destroyed in the Byzantine iconoclasm. The figural mosaics that exist today were made in the 10th-12th centures. This one of the theotokos is thought to reproduce the original 6th-century mosaic.

Muslim and Secular Phases

Hagia Sophia was turned from a church into a mosque when the Ottomans took over the city in 1453, and would remain so until Atatürk transformed it from a mosque into a museum in 1935. During its use as a mosque, Hagia Sophia underwent continual changes. Most notable are the four minarets that now stand at the corners of the building. Also, many of the Christian mosaics were plastered over so as not to interfere with the new Muslim function.

Smaller additions were made too, such as two massive Greek marble urns from Pergamon, added to the interior by Sultan Murad III in the 16th century. Importantly, many of the Christian features of the building were preserved under their layer of plaster so that they could be revealed when the building became a museum in 1935. Thus Hagia Sophia was able to display the many layers of history she had already survived.

It is clear from this long and turbulent history that Hagia Sophia can only be a monument to history if it is preserved intact. Thankfully, the Byzantine iconoclasm was the worst destruction suffered by the building so far. The current plan is to to use Hagia Sophia as a mosque – covering the images during services – but still to allow all visitors free access outside of services. If this is maintained, and if the integrity of the building and its history is cared for, Hagia Sophia will be able to serve as an unofficial museum for a long time yet.