On August 23, 2020, the Jewish Museum Berlin opened its new permanent exhibition. This was a mammoth project extending over the last 3 years. I went with a museologist friend to check it out – what a treat! Here is the report, starting with some outstanding positives and closing with some critical observations.

New Media to Good Effect

One great aspect of the new exhibition is its use of new media. The first hint is a music video right near the entry (sadly the headphones are blocked due to Corona – maybe there can be another solution introduced here). Later, there is a dark room with a huge screen for interviews with Jews about their daily practices. One of the most striking ones, to my mind, featured a rabbi who described her anxiety about her first son’s circumcision, and the contrasting feeling of righteousness directly following it. I liked the intensely personal and human element here.

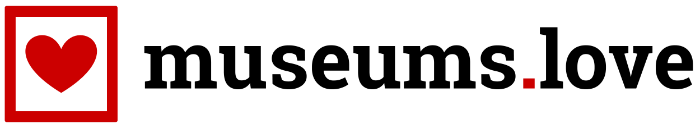

Audio media are also used to great effect. One long hallway (below) is lined with an undulating chain curtain and silver posts that emit music when touched. Push through the curtain and you find yourself in a primordially pink, uterine-like space with a curved couch reminiscent of a sixties living room, thrumming with an audio installation. This was the most sensorial part of the museum – for me to an uncomfortable degree, because it was so intimately anatomical.

Difficult Architecture

Libeskind’s building poses some problems for the visitor. It is utterly unforgiving in its one-directional axis, narrowing hallways, and confusing fake dead-ends. A look back into the first room shows how one-directionally it is oriented. The exhibits face the entering visitor, and turn their backs on the visitor leaving, going the “wrong” way, or wishing to revisit something. While a single path can feel nicely clear-cut, this extreme case seems to restrict movement.

Ultimately, this building is meant to be a monument in itself, as Libeskind’s concept clearly states. This creates challenges for its actual function, which is not simply to exist as an architect’s vision. In actuality, it is also supposed to be a box to hold things and welcome visitors to engage with. (How’s that for a definition of a museum! ICOM, take notes.) There is an absurd dissonance in hiring a star architect to build a museum building so spectacular that it impedes its use as a museum.

Some of the new displays are so minimalist as to go beyond harmonizing with the architecture. They seem almost to refuse to be a museum. They want to be pure steel walls, not display cases (photo at right). These slabs made me feel small, crushable, on edge. Perhaps Libeskind was aiming for this as part of reconstructing Jewish history, but I find it distracting.

A contrast to the linear trajectory of the visit is the lack of clear signposting about the big themes. Because most rooms of this exhibition don’t have wall text stating a title or theme, you have to figure out for yourself what common thread connects the displays. Although a DW reviewer mentions thematically-organized rooms, I have to wonder – did they get a cheat sheet? Or how long did they spend deciphering the themes? Another review says that the exhibition lets you “drift around,” but I just felt adrift. (Of the published reviews, I most agree with that in the FAZ.)

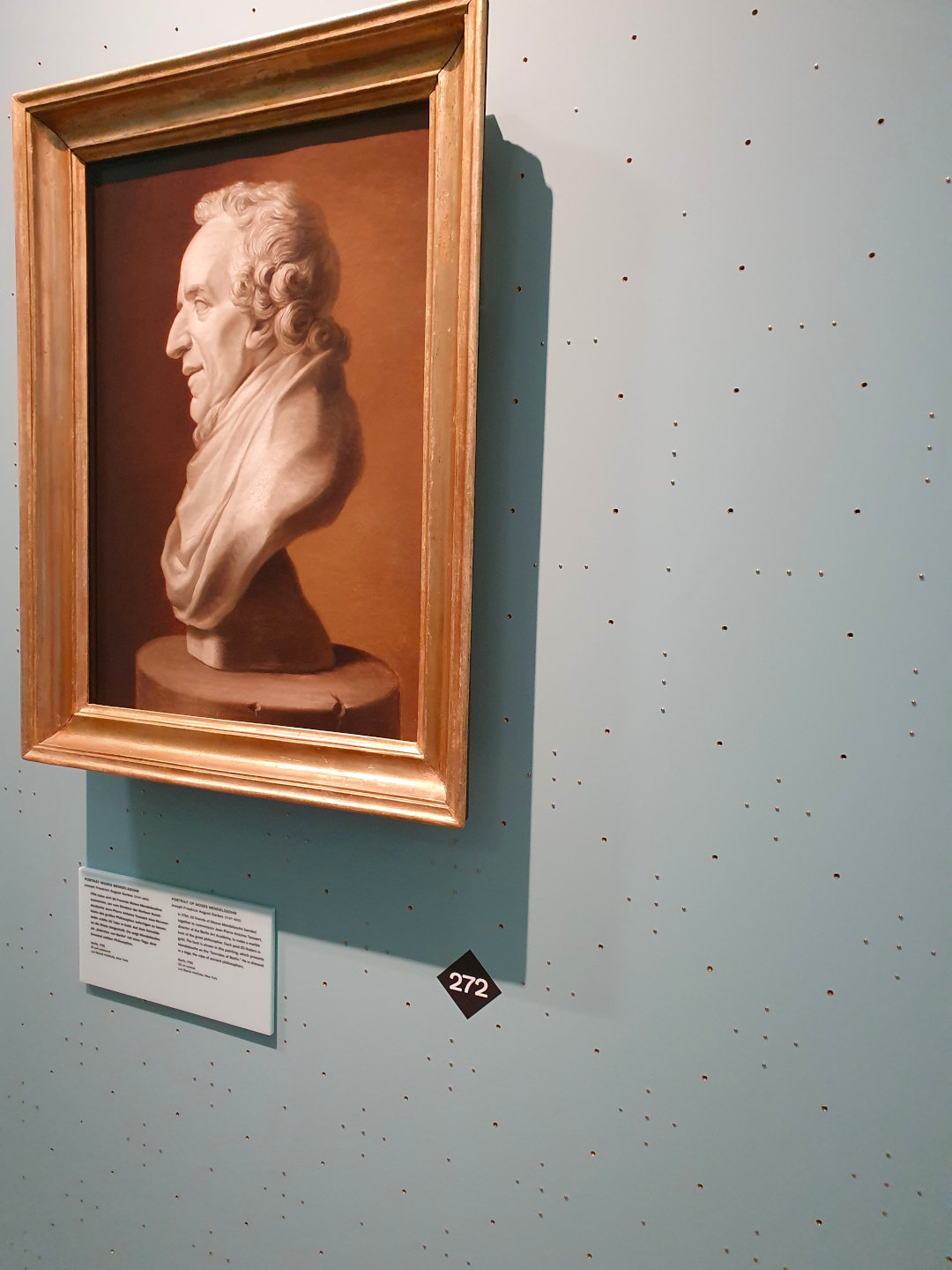

Because the objects are truly fabulous – laden with surprising or heart-rending stories – I would have liked to see them highlighted. How about a title in large font for each object, like: “Chinese marriage certificate for German Jewish emigrants to Shanghai.” Actually, that document is in a case with other objects that deserve the title “Shanghai: Haven for German Jews.” Isn’t that an unexpected and intriguing story? I certainly wanted to know a lot more about it.

Bravely Addressing Contemporary Issues: An Unfulfilled Wish

One theme that noticeably recurs throughout many galleries – for the visitor who reads an eye-straining number of small object texts – is the consistent persecution of Jews throughout their history. Numerous gigantic maps illustrate this (some unlabeled, which is frustrating). But I found myself wondering why this wasn’t addressed head-on as a problem that continues today. As antisemitism and the systematic exclusion of all sorts of groups is an intensely contemporary problem, why not highlight this as a current issue? Why not ask some questions that highlight the tragic but undeniable relevance to modern Berlin and modern Europe?

Questions like these could help promote active reflection and social change. And I’ve got a million. What was the basis for excluding the Jews in medieval Europe? Why were Worms and certain other cities safer for Jewish communities than other places? Why did the Weimar Republic finally abolish (in 1919) the last laws that singled out and punished Jews? Surely this was politically, and possibly economically, of interest at the time – what is the story there? How about Israel today – what about the Jews who live there now but don’t agree with the polarizing politics of the current regime?

There are so many contemporary issues that could be addressed by looking at Jewish history, it seems a shame to pass over them. Naturally, a museum can only do so much, and must choose its topics selectively. Yet of all museums, this museum could productively address these issues as no other could – because it is not only representing Jewish history, but representing Jewish history IN BERLIN, one of the most historically fraught places to do this.

Have you seen this exhibition, or that of another Jewish museum – perhaps the renowned one in New York? Or maybe you even worked on the JMB’s new exhibition and want to get in touch? Let me know in the comments; I’d love to hear from you!

Thank you for this thoughtful review of the JMB. I agree that there is a missed opportunity in not addressing growing anti-Semitism in Germany (not to mention all of the west), specifically Berlin, today. This is a complex issue with many facets, which is exactly why it merits documentation and discussion.

Absolutely. Surely the museum is communicating with other institutions (historical sites, House of One) to situate itself and its public offerings. Maybe even for its event programming, although I don’t see this on their website. I’d like to know more about what’s happening behind the scenes!