With numerous commemorative statues being toppled these days, those in front of museums have become a focus like never before. The American Museum of Natural History decided to remove the statue of Theodore Roosevelt from in front of the building because of protests (ongoing for years) about the way it depicts two figures, an African man and a Native man, behind the president. The museum had already created an exhibition about the statue and its controversy but decided to move it just last week, in light of the most recent protests.

Meantime, The Metropolitan Museum decided in the fall of 2019 to erect statues in the niches of the Fifth Avenue building’s facade – which had stood empty since construction ended in 1902. Obviously (or is it obvious?), the commission had to be contemporary in avoiding traditional hierarchies and histories, presenting instead a worldly vision befitting a cultural institution in the 21st century. Kenyan-American artist Wangechi Mutu met the challenge with grace and strength. She created four magnificent bronze statues whose monumentality suits the facade, but whose very modern forms ask us to think about what we expect from monumental statues. This is a brilliant way for a museum to engage with ongoing discussions in a constructive way.

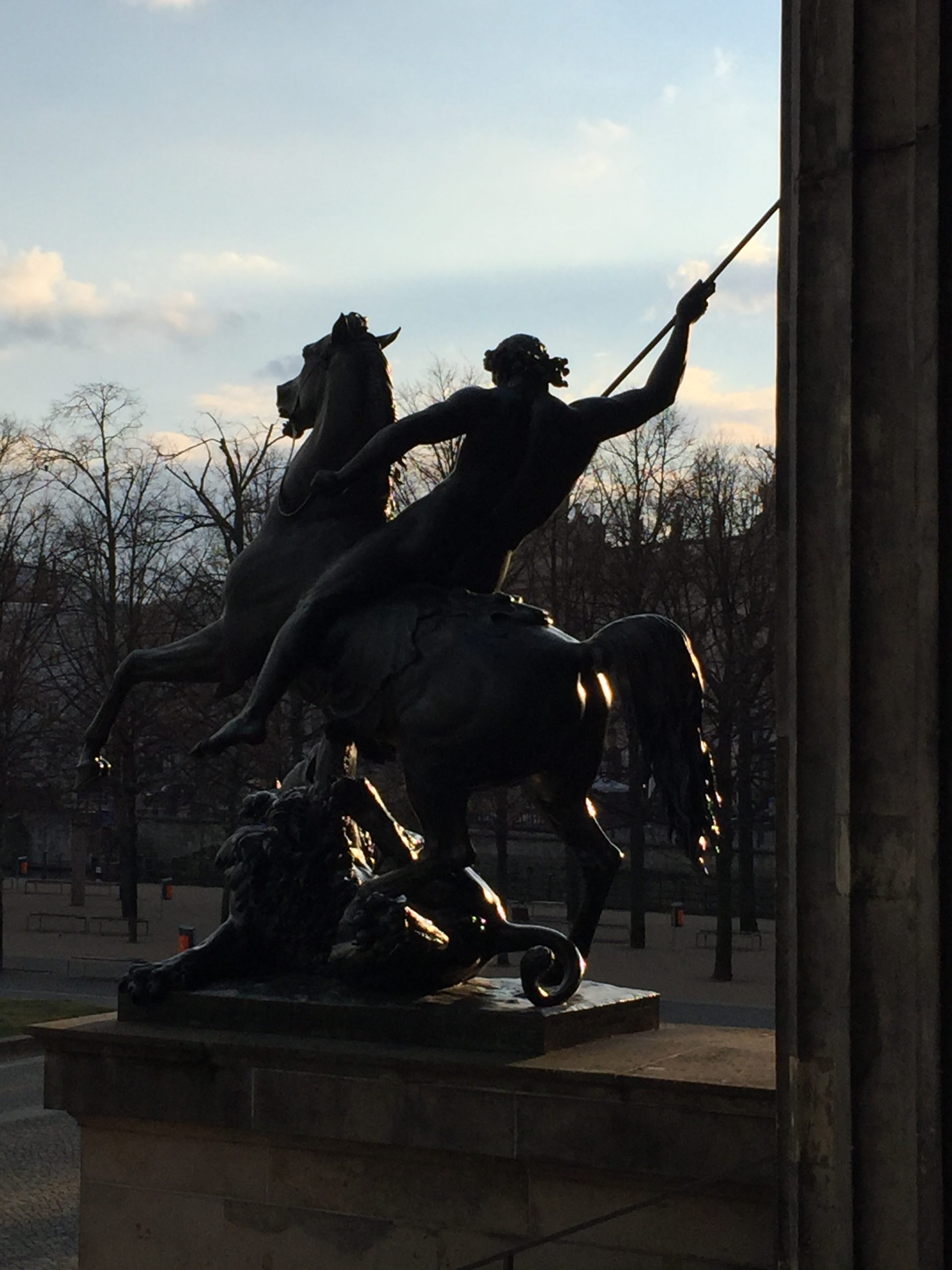

Both the destructive and constructive acts around statues – in front of museums, inside museums, and unrelated to museums – prompt us to reflect on the place of commemorative statues in our societies today. Do historical figures serve a purpose in this memorialized context? Do personifications or symbolic figures? (Like the Lion Fighter in front of Berlin’s Altes Museum, shown at right.) Artworks have a powerful effect on their human “interactors,” as current events attest. Museums are far from neutral spaces; to the contrary, they make decisions about what to display and how to display it. The statues in front of them are just the tip of the iceberg.