Hermaphrodite and gender in the museum

Start talking, not gawking

If you’ve seen my newest video, you know that ancient statues of Hermaphrodite have a lot to teach us. They help us reflect on both ancient and modern perceptions of gender and bodies. Ideally, how they are displayed in museums would leverage this power to start conversations on these topics. They could enrich museumgoers’ lives considerably.

Yet no museum I know seizes this opportunity. (Perhaps you know of one! Share it in the comments below!) Instead, the statues are given little context or mediation to help viewers understand and value them. This means that they are often surrounded by tourists taking photos to show their friends, snickering about a body type they consider funny, and perhaps arousing. Large groups snapping photos of the famous “sleeping Hermaphrodite” statue in the Louvre are positively disturbing. Body shaming, bigotry, and sexual assault should be countered by museums, not encouraged. Even visitors who are deeply interested in the statue’s significance are left asking, Is this really just a funny picture? Is that all that Hermaphrodite was in antiquity too?

Museums can lead the way!

The change needs to start with museum presentation before we can expect it to spread through our society. Museums, after all, are the places for people to learn about living on this planet. Museums must stop calling the sculpture of a satyr sexually assaulting Hermaphrodite as “playful” and “titillating.” They must stop referring to Hermaphrodite as “he,” and stop exhibiting Hermaphrodite statues in places that encourage viewers to fetishize these bodies as implicitly sexualized or freakish. Instead, Hermaphrodite needs to be displayed with honesty, sensitivity, and encouragement to reflect.

Further Reading

- This excellent essay on being transgender combines a first-person perspective with a scholar’s view of ancient sculpture – and revising this view based on personal experience.

- A chapter in the book Naked Truths. Women, sexuality and gender in classical art and archaeology presents the theory that Hermaphrodite was a cult figure. See the chapter “The Only Happy Couple. Hermaphrodites and Gender” by Aileen Ajootian (preview available here).

- The book Looking at Laughter by John Clarke is a foundational work for understanding Roman humor. Beware: this may irredeemably lower your opinion of the Romans forever…

- This article admirably addresses the ongoing culture of sexual assault in art, from antiquity to the present. Unfortunately it is not freely available, but perhaps some communication with the author or press could change that: Ethics and Erotics: Receptions of an Ancient Statue of a Nymph and Satyr

- The fairly new book Gender, Identity and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture includes a chapter on Hermaphrodite. It is a fairly standard introduction to the artworks and concepts, but not quite as progressive as one might have hoped.

Have you seen Hermaphrodite artworks in museums? Share your thoughts in the comment section below!

Music Videos in Museums

A revelation has come with the new music video for the song “Dorado” by Italian rapper Mahmood. In it, the artist is shown in various locations – one of which is the “Gallery of the Kings” in the Museo Egizio in Turin. This dramatic hall is the perfect setting for Mahmood to dance and rap in part about Egypt – where his father was born. What a fabulous collaboration between modern music artist and museum! It’s beneficial to both sides. Mahmood’s video gets an evocative setting, and the museum is benefitting significantly from the press about the video. Museum director Christian Greco even gave Mahmood a tour around – another great photo op, of course, and great publicity for the museum. It shows not only the museum’s openness to allowing filming on their premises, but active embracing of the vibrant arts community.

Are other museums doing the same? So far, there haven’t been many music videos filmed in museums – but there are a few must-sees.

Perhaps most famously, The Carters (Beyoncé and Jay-Z) shot the music video for their song “Apeshit” in the Louvre. The video is a smart and visually stunning statement that certainly won over new fans for the museum.

This week the French artist Jain released a video shot in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The project was supported by YouTube and the museum itself is featured on Google Arts and Culture – indicating a new way to produce cultural content in future that reaches potentially huge audiences worldwide.

K-Pop (Korean pop) legend BTS released a music video for their song “Blood Sweat & Tears” that includes a scene in a museum – but no one has been able to find out what museum it might represent (the V&A is indeed similar but has a different floor and objects). Perhaps it was a specially constructed set.

Tim Baker released a music video for “Dance” last year that was shot in the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Canada. The video is such a beautiful sonnet to the museum that it could be made into powerful advertising – although the museum’s website sadly doesn’t seem to mention it.

In earlier history, German electronic hip hop band Deichkind filmed part of their 2014 music video for “So ‘ne Musik” in an art museum – but which one? Perhaps somewhere in Hamburg, the band’s hometown?

Finally, museums can reach new audiences through music videos created by visitors themselves. Both the Children’s Museum of the Arts New York and the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago have offered family workshops on the topic. A fun idea. Now we can hope for more music videos shot in museums in future to push this movement forward!

Do you know of other music videos shot in museums? Let us known in the comments below!

Hagia Sophia: Istanbul's Church, Mosque, Museum

The Turkish president Erdogan’s recent decision to change Hagia Sophia from a museum back into a mosque is significant. The political implications are discussed by experts elsewhere. Here, let’s take a look at the remarkable museum that Hagia Sophia was and, if all goes well, may unofficially remain. What is so significant about this place that it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is consistently one of Turkey’s most-visited attractions? What about the building makes it a museum, and what are its exhibits?

Byzantine Phase

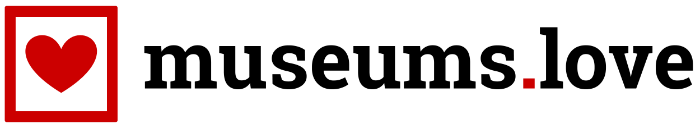

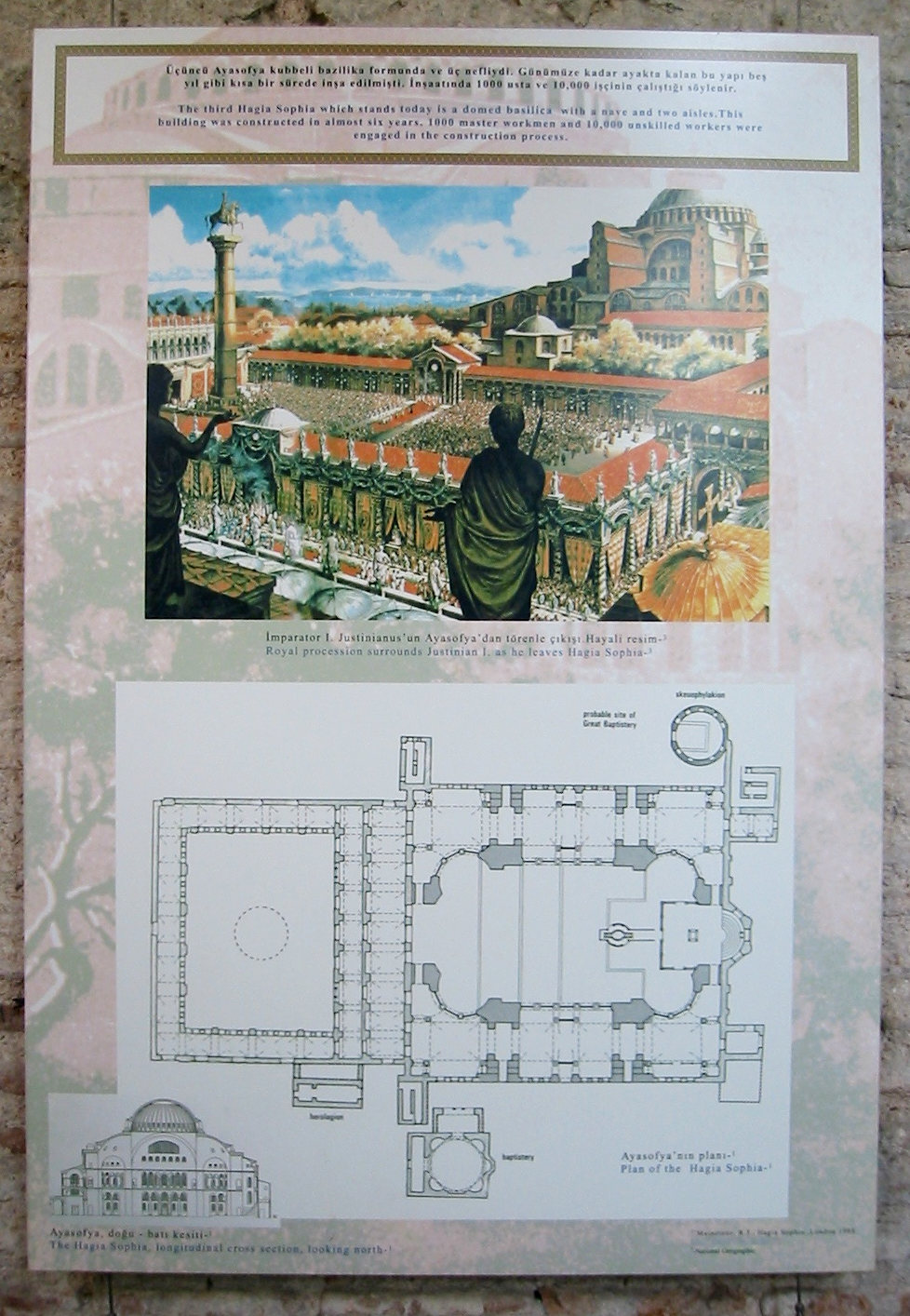

Architecturally, Hagia Sophia is a pioneer. Its use of vaults was unprecedented when it was built in the mid-6th century AD, back when Istanbul was the Byzantine capital city Constantinople. The huge central dome balances atop a cascade of smaller domes and vaults, which support its huge weight. It was the biggest dome in the world for over 1000 years! (Surpassed only by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in the Renaissance.) In this stage of Hagia Sophia’s long life, the building served as a church – and an expression of power for Justianian, the emperor who commissioned it.

Although Istanbul’s cityscape certainly looked different in the 6th c. AD than it does now, it was every bit as cosmopolitan and urbanized. Some signs in Hagia Sophia, although scarce and old, give an impression of this. It will be interesting to see whether such signage will find a place in Hagia Sophia after it is no longer officially a museum.

Artistically too, the Byzantine building is a treasure. The marble capitals on the columns are carved in an intricate “basketweave” form, and the gilded mosaics on the walls and ceilings are breathtaking. Marble panels on the walls display the “butterfly” or “bookmatching” technique, in which two panels cut adjacently from the same block are opened outward from their common surface (like opening a book) and attached to the wall side-by-side to show off their symmetrical pattern.

In the center of the main dome is a mosaic depicting Mary holding the baby Jesus. They are surrounded by a gold surface that highlights their divinity. Both the divinity of Mary and her pose here as the bearer of God, or theotokos, reflect important developments in the early Christian church and iconography at the time. Mary was acknowledged as theotokos at one of the numerous church councils held in this period. Tragically, every single one of Hagia Sophia’s original 6th-century figural mosaics were destroyed in the Byzantine iconoclasm. The figural mosaics that exist today were made in the 10th-12th centures. This one of the theotokos is thought to reproduce the original 6th-century mosaic.

Muslim and Secular Phases

Hagia Sophia was turned from a church into a mosque when the Ottomans took over the city in 1453, and would remain so until Atatürk transformed it from a mosque into a museum in 1935. During its use as a mosque, Hagia Sophia underwent continual changes. Most notable are the four minarets that now stand at the corners of the building. Also, many of the Christian mosaics were plastered over so as not to interfere with the new Muslim function.

Smaller additions were made too, such as two massive Greek marble urns from Pergamon, added to the interior by Sultan Murad III in the 16th century. Importantly, many of the Christian features of the building were preserved under their layer of plaster so that they could be revealed when the building became a museum in 1935. Thus Hagia Sophia was able to display the many layers of history she had already survived.

It is clear from this long and turbulent history that Hagia Sophia can only be a monument to history if it is preserved intact. Thankfully, the Byzantine iconoclasm was the worst destruction suffered by the building so far. The current plan is to to use Hagia Sophia as a mosque – covering the images during services – but still to allow all visitors free access outside of services. If this is maintained, and if the integrity of the building and its history is cared for, Hagia Sophia will be able to serve as an unofficial museum for a long time yet.

Diversity and Community Inclusion in Museums

My newest video focuses on diversity in the ancient art of Berlin’s Altes Museum. It offers a perfect chance to collect some of the wonderful resources that museums are putting out to reach their diverse audiences, and to draw attention to this pressing issue. Here is a brief collection of some of my favorites. Please comment below with further ideas!

- The Myseum of Toronto is a paragon of Community Responsive Programming. This museum doesn’t even have a building – it consists purely of initiatives that go out into the community to make a difference!

- I love the idea of a Social Justice Curator. Jasmine Wahi at the Bronx Museum of the Arts is making use of this position by putting on exhibitions and much more about pressing social issues. One statement in her interview for ArtNews struck me in particular: “The paintings Khari [Turner, artist] showed me were saturated with color, and evoked a sense of jubilation. Moments of joy are so important right now: social justice in art is not just about illustrating injustice. It’s also about fighting for our right to be joyful.” Check out the Bronx Museum’s list of social justice resources here.

- The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow put untold thought, passion, and resources into reaching their community during the pandemic. They particularly built up their programming for autistic and hearing-impaired visitors. Inspiring not just for our vision of museums, but of humanity!

The video “White at the Museum” by the Lucas Brothers (shown on Full Frontal with Samantha Bee) is a highly entertaining look at the very serious subject of whitewashing Greek and Roman art. It is exactly the right dose of academic learning mixed with social responsibility and, yes, humor.

Have you discovered other ways that museums are using to prioritize diversity and community inclusion? Let us know below in the comments!