Review: Dali Museum Berlin

After years of seeing its advertisements hanging from lampposts around the city, I finally visited Dali: The Exhibition on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin (at first a traveling exhibition, sedentary since 2009). Most of the hundreds of objects on display here are works on paper – mostly in printing techniques – supplemented by a few small sculptures and a video. It was thrilling to see these works after learning about the artist in the fabulous BBC documentary by Alastair Sooke!

Dali manipulated printing media to create astounding effects that often resemble watercolor or ink drawing. You can see this in the illustration at right, from the series he did for an Alice in Wonderland edition. Soft clouds of color combine with crisp black shapes arranged like a violent splatter. These same effects are omnipresent in Dali’s works on paper: flowing masses of color next to small, sharp, black forms evoking stretched shadows, insects, or calligraphy. Aha, there are those subconscious associations that the Surrealists were so keen on exhuming!

Another series of prints looks astonishingly like pen-and-ink drawings. Each picture focuses on a single figure with some hint of a landscape to stand on, and a Surrealist dose of body parts growing unexpectedly out of voids and objects. Some details reminded me strongly of the Surrealist parlor games, such as the exquisite corpse.

The printing technique of lithography is highlighted in one exhibit that shows, step by step, how a color print was made from many layers of single colors. An incomplete print hung on the wall is followed below by a print of the single color layer that was added to it in the next step. Below that is the print now featuring that layer. And so on – over more than fifteen steps! You certainly gain an appreciation for the complexity of the process.

A wonderful video by MOMA illuminates the complex process of lithography.

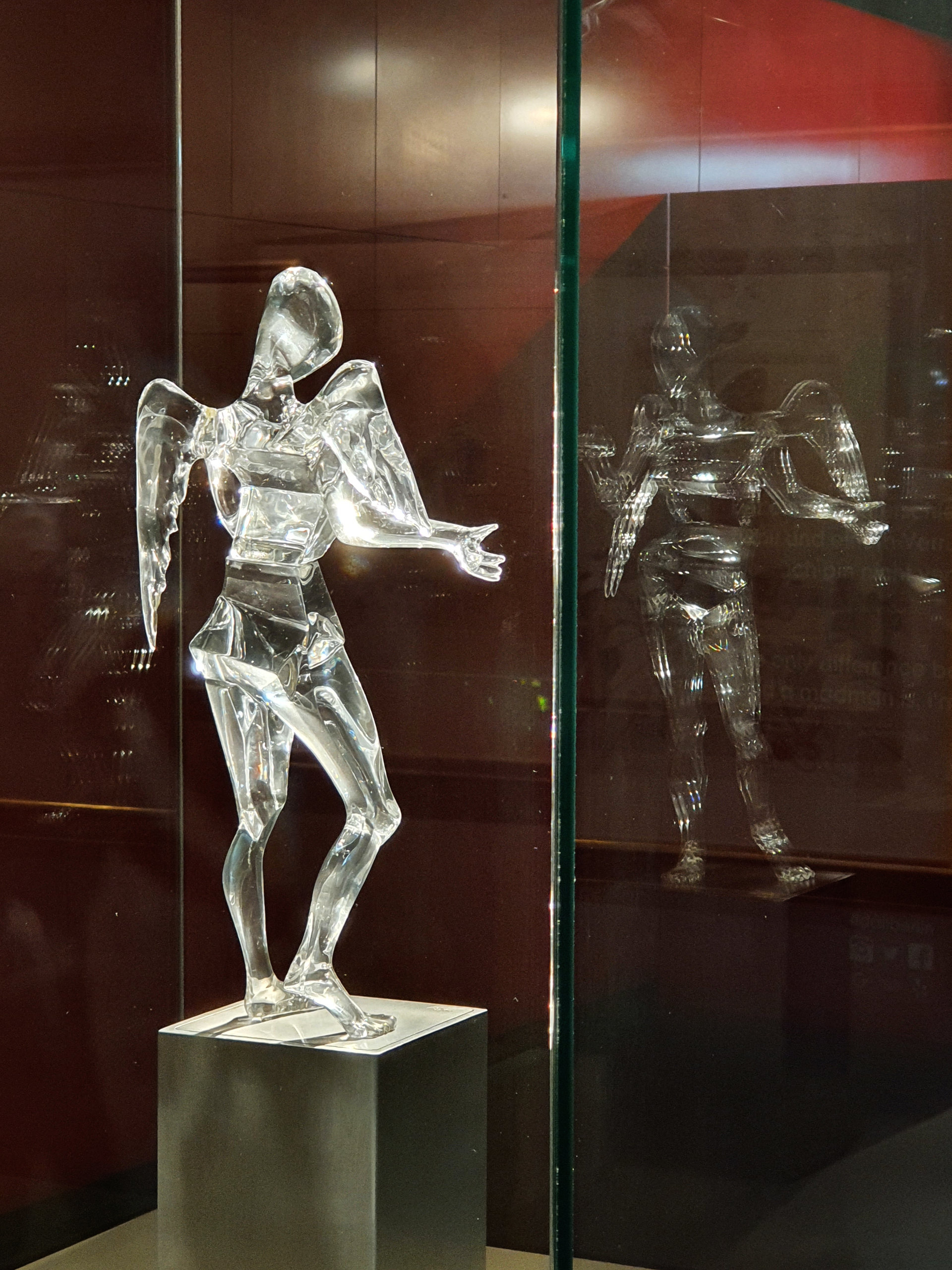

Several small-scale sculptures round out the display. The most ethereal (and best lit!!) has to be this winged figure right near the exit (and gift shop). Although it is hardly as typical of Dali as the many other works shown here, it reminds us of the artist’s wide-ranging interest in media of all sorts. This included commercial ventures like television ads and, as our wonderful tour guide Anneke told us, the wrapper design for Chupa-Chup lollypops! You’ll find those in the gift shop too, of course.

Overall, this museum contains perhaps the least text I have ever seen in a museum. Individual works have essentially no decipherable labels; series are named in a simple title and date. This certainly suits the international, multilingual tourist audience – and it also aligns with the Surrealist desire to uncover pan-human experiences, in part by inviting viewers to interpret artworks however they (and especially their subconscious) see fit. Even so, the 45-minute tour is a supplement that is definitely worth considering; our tour guide was incredibly enthusiastic and knowledgeable.

Have you had a Surrealist experience in a museum? Let me know in the comments section below – I’d love to hear from you!

Exhibition Review: What Can Hannah Arendt Still Teach Us?

For one more month, an exhibition about Hannah Arendt is on show in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. Although I knew the name of this famous philosopher and author who fled Nazi Germany, I wanted to find out more about her after having recently visited two concentration camps and read a haunting survivor’s account in graphic novel format.

One of the landmark photographs of Arendt (right) captures the imposing presence of her person. Indeed, this is one of the accomplishments of the exhibition: it gives a full picture of Arendt as a person, from her early scholarship through many decades of important and controversial engagements in Germany, the USA, and Israel. One of my favorite parts of the exhibition is the videos of Arendt speaking in interviews, precisely because they show the person behind the momentous social philosophies she formulated.

Another memorable exhibit sticks in my mind (below). This is the model of the extermination complex at Auschwitz, modeled by Polish sculptor Mieczyslaw Stobiers. It is juxtaposed here with Arendt’s work about the Nazi state as a model of totalitarianism. Stobiers made this piece for this museum in 1994-95, nearly fifty years after he made his first model of it. During those many years he made even more. To me this was a heartrending relic of a life irrevocably affected by Nazism, and a lifetime spent painstakingly commemorating it. It seems like it must be horrible for the sculptor to relive each detail of this godawful place, not just once but with every new model – and yet maybe there is not just trauma, but also therapy in that act.

What I missed in this exhibition was a clear statement about what makes Arendt so important, and what her thoughts or philosophical formulations really were. Maybe the curators assume that we know that already, but I don’t – or not beyond some key terms like the “banality of evil.” Presenting these at the beginning would have helped me understand the wide-ranging chronological and thematic sections to come, starting with German-Jewish salon culture, extending through Arendt’s view of colonialism, to her famous report on the Eichmann trials, and her confrontation with 1950s American racism and German post-war revisionism. Maybe Arendt’s life is too much to sum up in an exhibition, no matter how expansive. But this show does a good job of introducing the range of subjects that Arendt managed to influence in her lifetime, not to mention the many controversies she sparked.

Even more, I would have liked a clear statement linking Arendt’s work with present-day issues. The connection is doubtless in the curators’ minds – Arendt’s words can be eerily contemporary! But why not stand up and say it out front, right in the title of the show? “Hannah Arendt and the Twentieth Century” should actually be “Hannah Arendt and the Twenty-First Century.” Better, it could drop the lame conjunction “and” and take a stand instead:

Hannah Arendt: Chilling Lessons for the Twenty-First Century

In any event, the exhibition inspired me to read Arendt’s groundbreaking The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem. Sadly I didn’t see these works by Arendt in the museum shop – only books of her correspondence, and books about her. I look forward to getting hold of them elsewhere.

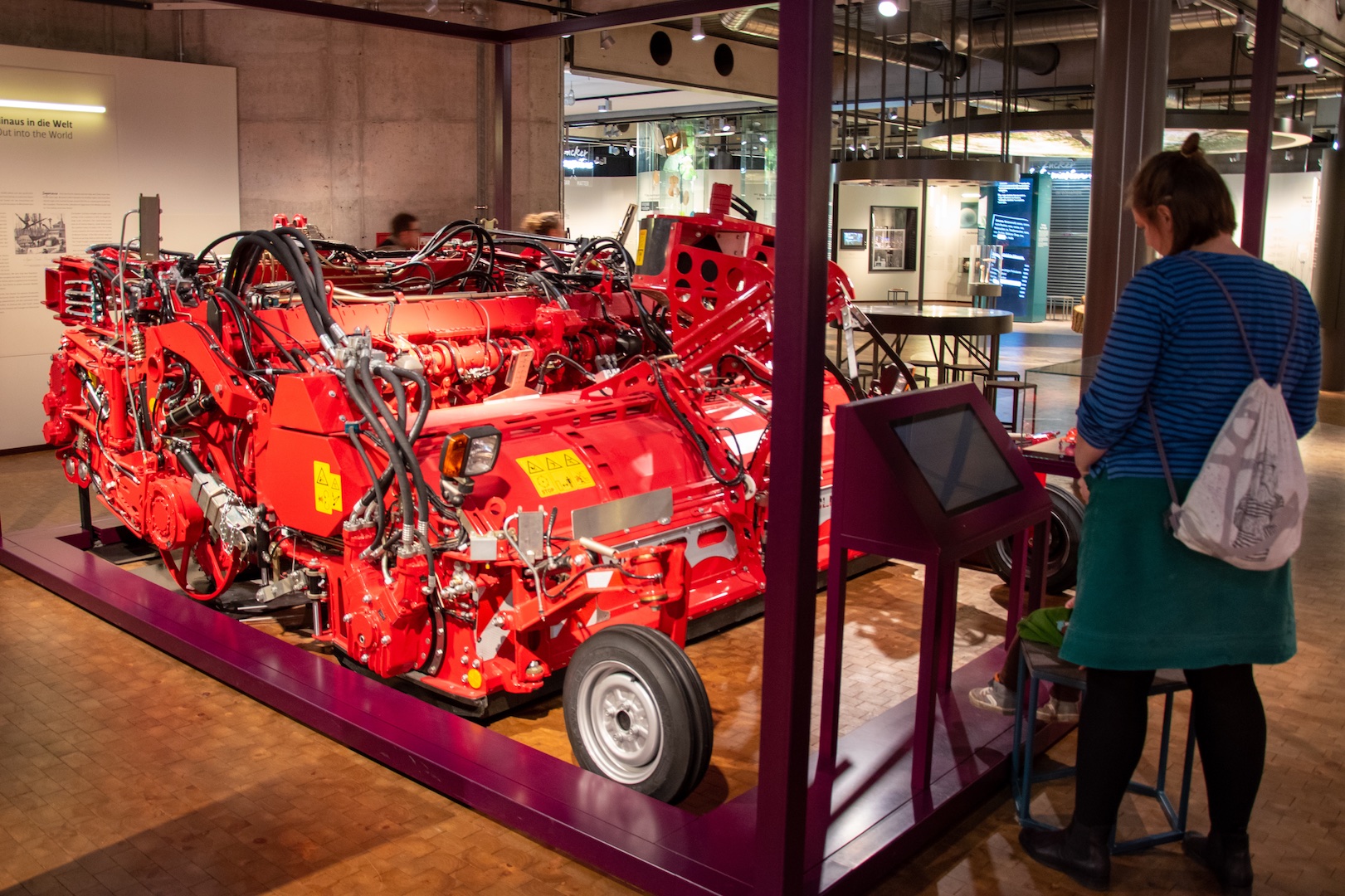

All About Sugar in Berlin

This is the best-kept museum secret for visitors to Berlin. “Alles Zucker / All About Sugar” is a fantastic permanent exhibition in the German Technical Museum, and it’s all bilingual in German and English. You can learn a huge deal here with these accessible and lively displays. They uncover the chemistry of sugar (that huge crab in the photo below is made of sugar…but not what you expect!) as well as its stormy history, in which Berlin plays a surprising star role. That’s right: Berlin was the source of the first-ever European sugar! Find out all about it in my podcast episode—you’ll learn smarty-pants things to impress even the most elite Berlin insiders.

Plus, check out the museum’s other enticing interactive exhibits in my video here!

New Exhibition: Impressionism in the Museum Barberini, Potsdam

Museum Barberini

One of the most striking private museums in Germany has to be the Museum Barberini. Contrary to the name, it owes its existence not to a Barberini but to Germany’s version of Bill Gates, a man named Hasso Plattner, a founder of SAP software. Plattner had the building constructed after a palazzo that stood on the site until WWII, but reinvented the interior to be more functional as a museum. The museum’s exhibitions are based on Plattner’s own wide-ranging art collection, from GDR artists to Warhol and – you guessed it! – Impressionists.

The first gallery (below) displays the history of the building, from the original Palazzo Barberini to the current museum. The interior courtyard (right) houses a sculpture by famous GDR artist Wolfgang Mattheuer, as well as a scenic cafe (around the corner to the right).

Impressionist Exhibition

As for the current exhibition of Impressionists, the artworks are breathtaking. Both well-known and more obscure paintings are included. And what a pleasure to be allowed to photograph them! This is one benefit of a private collection: the owner can decide to allow photography. The picture above shows two works juxtaposed in a room of paintings of harbors. (I wondered whether the matching off-white canvas inserts inside the frames, clearly added in one concerted action, were fillers to compensate for frames that were too large – ?) This generally thematic organization of the galleries, as well as the erudite historical texts in the labels, is a very standard way to display art. Yet even if the display didn’t set my curatorial heart beating faster, we can surely agree that we go to such a show to see the masterpieces, not the way they are displayed.

Private Museums

This is a great chance for the public to see art which, in the hands of other collectors, might easily have been locked into a freeport storage unit, never to see the light of day, fulfilling its purpose as an investment simply by existing. By contrast, showing art to the public is a benefit to the public and – depending on the applicable tax laws – to the donor. Ideally, it’s a win-win situation.

So should we hope for a Bill Gates Museum of Pop Art and a Warren Buffett Museum of Surrealist Painting? Or more extreme: should we stop paying taxes to sometimes lamentably inefficient state-run museums and entrust private donors to pick up the slack?

Private museums are wonderful enrichments to the cultural landscape, but one aspect of them requires careful reflection. A private donor is a single individual with personal preferences that influence their actions in creating a museum more than is possible in a team-based organization without a private patron. In the museum world, important private donors can influence the entire cultural landscape based on their own preferences. If Hasso Plattner had collected not Monets but plastic shopping bags from divided Germany, and displayed these in the museums, this genre of visual culture would have become much more well-known and high-value. The art market would change, and future art history textbooks might even include plastic bags. This sort of one-person influence is also present in the figure of the museum curator making decisions about accessioning and deaccessioning certain artworks in their collection; the phenomenon is simply magnified in the one-patron institution.

Similarly, certain values are expressed in the architecture of the Museum Barberini – ike any privately-built building – that reflect the donor’s wishes (in agreement with the local civic bodies, of course). If a different donor had come into Potsdam championing Zaha Hadid architecture, you can bet that the museum would look different! And it would make a different statement in the cityscape: a gesture toward Middle Eastern culture, modernism, and feminism, for instance. So here too, the power of a single donor defines not only the end result, but its message to the surrounding community.

Hopefully, in any given cultural area, there are enough state-run and generally diverse, team-based institutions to balance out such potential imbalances. Private museums have a lot to offer their communities. A perfect museum world has space for both public and private institutions, creating a plurality of perspectives.

What private museums have caught your attention lately? Let me know here in the comments, or via the Contact page – I’d love to hear from you!

Stone Age meets Modern Media in Bilzingsleben

(Watch the accompanying video here.)

I love surpises. And museums. So a surprise museum is a gift, and a GOOD surprise museum is a jackpot! In all these respects, the Ausgrabungsstätte Steinrinne Bilzingsleben (website in German) is the cat’s pajamas. This “stone channel” archaeological site is tucked away in the village of Bilzingsleben in Thuringia, Germany, surrounded by fields of grain. On vacation there recently, I awoke with the farmers driving their tractors by the hotel at daybreak. Yes, rural! A museum was about the last thing I expected from this place. Or, to be honest, a GOOD museum was really the very last thing I expected. Thank you for proving me wrong, Bilzingsleben!

While the uninitiated like me wouldn’t know it, this village is actually famous in certain circles: palaentology circles, to be precise. Bilzingsleben’s fertile ground has yielded up three ancestral human bodies of a distinct type, thereafter named homo erectus bilzingslebenensis. You can read all about the site and its significance (in English) here. A professor at a nearby university made it his life’s work to excavate this area and turn it into a beautiful museum. Enough funding was rounded up to build the hallmark curved-roof construction, as well as install a fabulous display. The people working in the booth at the entrance were hugely knowledgeable, enthusiastic, and welcoming, and answered a lot of questions after my visit. (Plus they gave me a cool coin… watch my video to find out the story there!) This is quite clearly a labor of love for many people.

Inspired by the experience, I wanted to give you a look inside; so I made a mini-video about it once I got home. Enjoy! And consider making Bilzingsleben a stop on your next European adventure. (If your German isn’t great, be sure to engage a friendly tour guide or Google Translate for your visit.) The unique (and heartwarming!) experience here – combining the landscape, display, and friendly people – definitely makes my Top 5 list of favorite museum visits in Europe.

What’s on your list of Top 5 favorite museum visits? Let me know here in the comments, or via the Contact page – I’d love to hear from you!