All About Sugar in Berlin

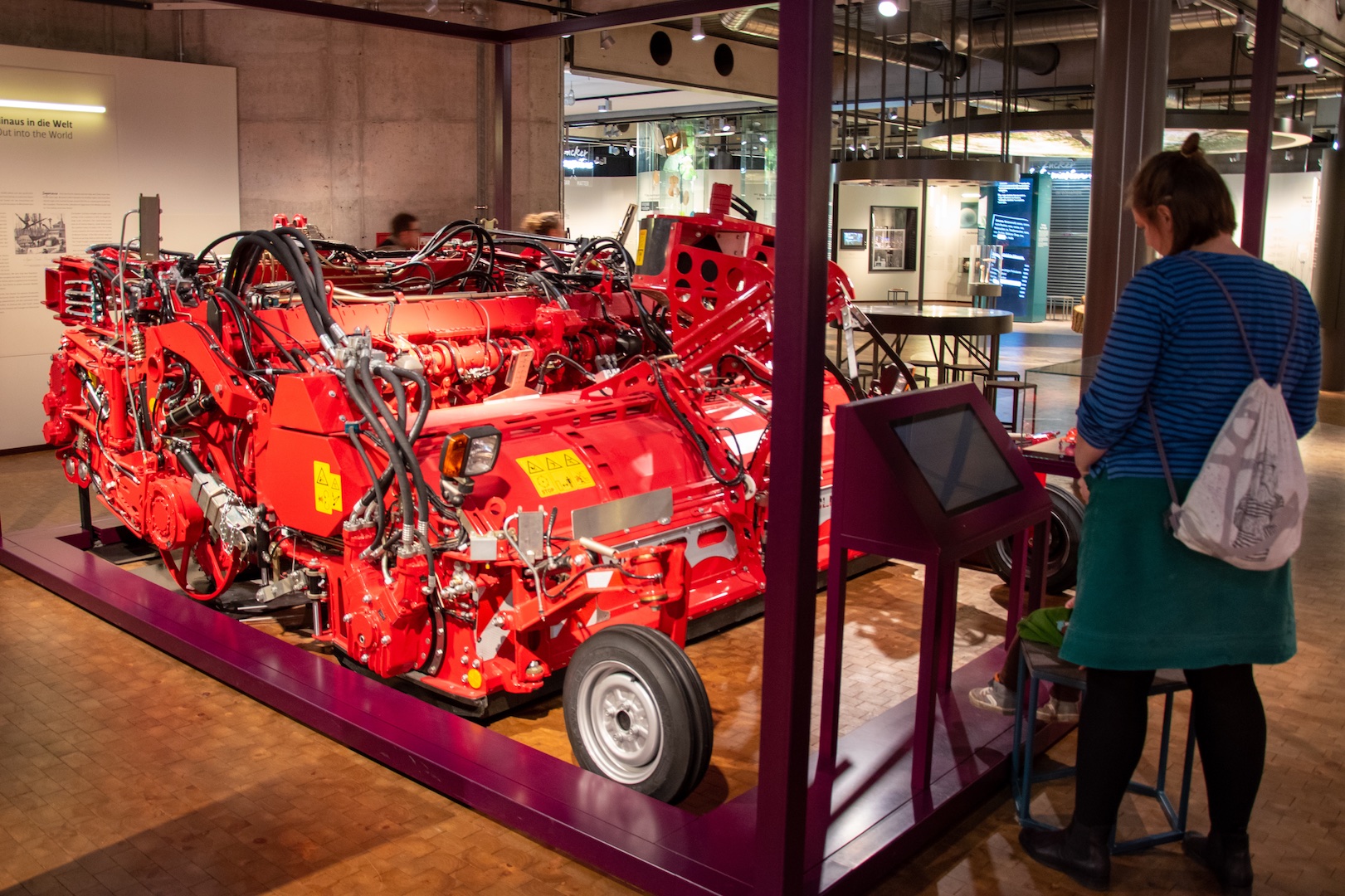

This is the best-kept museum secret for visitors to Berlin. “Alles Zucker / All About Sugar” is a fantastic permanent exhibition in the German Technical Museum, and it’s all bilingual in German and English. You can learn a huge deal here with these accessible and lively displays. They uncover the chemistry of sugar (that huge crab in the photo below is made of sugar…but not what you expect!) as well as its stormy history, in which Berlin plays a surprising star role. That’s right: Berlin was the source of the first-ever European sugar! Find out all about it in my podcast episode—you’ll learn smarty-pants things to impress even the most elite Berlin insiders.

Plus, check out the museum’s other enticing interactive exhibits in my video here!

New Exhibition: Impressionism in the Museum Barberini, Potsdam

Museum Barberini

One of the most striking private museums in Germany has to be the Museum Barberini. Contrary to the name, it owes its existence not to a Barberini but to Germany’s version of Bill Gates, a man named Hasso Plattner, a founder of SAP software. Plattner had the building constructed after a palazzo that stood on the site until WWII, but reinvented the interior to be more functional as a museum. The museum’s exhibitions are based on Plattner’s own wide-ranging art collection, from GDR artists to Warhol and – you guessed it! – Impressionists.

The first gallery (below) displays the history of the building, from the original Palazzo Barberini to the current museum. The interior courtyard (right) houses a sculpture by famous GDR artist Wolfgang Mattheuer, as well as a scenic cafe (around the corner to the right).

Impressionist Exhibition

As for the current exhibition of Impressionists, the artworks are breathtaking. Both well-known and more obscure paintings are included. And what a pleasure to be allowed to photograph them! This is one benefit of a private collection: the owner can decide to allow photography. The picture above shows two works juxtaposed in a room of paintings of harbors. (I wondered whether the matching off-white canvas inserts inside the frames, clearly added in one concerted action, were fillers to compensate for frames that were too large – ?) This generally thematic organization of the galleries, as well as the erudite historical texts in the labels, is a very standard way to display art. Yet even if the display didn’t set my curatorial heart beating faster, we can surely agree that we go to such a show to see the masterpieces, not the way they are displayed.

Private Museums

This is a great chance for the public to see art which, in the hands of other collectors, might easily have been locked into a freeport storage unit, never to see the light of day, fulfilling its purpose as an investment simply by existing. By contrast, showing art to the public is a benefit to the public and – depending on the applicable tax laws – to the donor. Ideally, it’s a win-win situation.

So should we hope for a Bill Gates Museum of Pop Art and a Warren Buffett Museum of Surrealist Painting? Or more extreme: should we stop paying taxes to sometimes lamentably inefficient state-run museums and entrust private donors to pick up the slack?

Private museums are wonderful enrichments to the cultural landscape, but one aspect of them requires careful reflection. A private donor is a single individual with personal preferences that influence their actions in creating a museum more than is possible in a team-based organization without a private patron. In the museum world, important private donors can influence the entire cultural landscape based on their own preferences. If Hasso Plattner had collected not Monets but plastic shopping bags from divided Germany, and displayed these in the museums, this genre of visual culture would have become much more well-known and high-value. The art market would change, and future art history textbooks might even include plastic bags. This sort of one-person influence is also present in the figure of the museum curator making decisions about accessioning and deaccessioning certain artworks in their collection; the phenomenon is simply magnified in the one-patron institution.

Similarly, certain values are expressed in the architecture of the Museum Barberini – ike any privately-built building – that reflect the donor’s wishes (in agreement with the local civic bodies, of course). If a different donor had come into Potsdam championing Zaha Hadid architecture, you can bet that the museum would look different! And it would make a different statement in the cityscape: a gesture toward Middle Eastern culture, modernism, and feminism, for instance. So here too, the power of a single donor defines not only the end result, but its message to the surrounding community.

Hopefully, in any given cultural area, there are enough state-run and generally diverse, team-based institutions to balance out such potential imbalances. Private museums have a lot to offer their communities. A perfect museum world has space for both public and private institutions, creating a plurality of perspectives.

What private museums have caught your attention lately? Let me know here in the comments, or via the Contact page – I’d love to hear from you!

Stone Age meets Modern Media in Bilzingsleben

(Watch the accompanying video here.)

I love surpises. And museums. So a surprise museum is a gift, and a GOOD surprise museum is a jackpot! In all these respects, the Ausgrabungsstätte Steinrinne Bilzingsleben (website in German) is the cat’s pajamas. This “stone channel” archaeological site is tucked away in the village of Bilzingsleben in Thuringia, Germany, surrounded by fields of grain. On vacation there recently, I awoke with the farmers driving their tractors by the hotel at daybreak. Yes, rural! A museum was about the last thing I expected from this place. Or, to be honest, a GOOD museum was really the very last thing I expected. Thank you for proving me wrong, Bilzingsleben!

While the uninitiated like me wouldn’t know it, this village is actually famous in certain circles: palaentology circles, to be precise. Bilzingsleben’s fertile ground has yielded up three ancestral human bodies of a distinct type, thereafter named homo erectus bilzingslebenensis. You can read all about the site and its significance (in English) here. A professor at a nearby university made it his life’s work to excavate this area and turn it into a beautiful museum. Enough funding was rounded up to build the hallmark curved-roof construction, as well as install a fabulous display. The people working in the booth at the entrance were hugely knowledgeable, enthusiastic, and welcoming, and answered a lot of questions after my visit. (Plus they gave me a cool coin… watch my video to find out the story there!) This is quite clearly a labor of love for many people.

Inspired by the experience, I wanted to give you a look inside; so I made a mini-video about it once I got home. Enjoy! And consider making Bilzingsleben a stop on your next European adventure. (If your German isn’t great, be sure to engage a friendly tour guide or Google Translate for your visit.) The unique (and heartwarming!) experience here – combining the landscape, display, and friendly people – definitely makes my Top 5 list of favorite museum visits in Europe.

What’s on your list of Top 5 favorite museum visits? Let me know here in the comments, or via the Contact page – I’d love to hear from you!

Museum + Hotel = Trend of the Future?

After nearly ten years of construction, an incredible new museum has opened at a famous archaeolgical site in Turkey. What makes Antakya (ancient Antioch) special is now longer “just” the archaeology – itself spectacular – nor its disputed status between Turkey and Syria, but an entirely new model of museum. The Turkish firm EAA – Emre Arolat Architecture conceived “The Museum Hotel,” a building that hovers over an open-air museum. The museum showcases some of the best-preserved Roman-era mosaics in the world (image above by Dosseman; see more pictures on the linked websites).

It’s a mind-bogglingly ambitious design. It consists of space-age containers that, by virtue of warm colors and a configuration resmbling peeping out from under a blanket, appear as cozy as an Alpine auberge. The ultra-refined interiors of the hotel rooms, reception, restaurant, and bar take best advantage of the views over the ancient remains. And of course the mosaics are used as a motif in the elegant interior decoration. The original Roman mosaics that inspired the design can be seen in the local Antakya Archaeological Museum, including the fragment at right.

Bowled over by this concept and design, I racked my brain for parallels. The closest I could come up with are the art hotels that feature contemporary art in the rooms to create a special “near art” experience – but The Museum Hotel is another thing altogether, almost taking the place of a visitor center on the site. Could this be a trend of the future, as cultural heritage sites continue to require funding and interpretation beyond public financial means?

Do you know of more examples like this? Let me know here in the comments, or via the Contact page – I’d love to hear from you!

Hermaphrodite and gender in the museum

Start talking, not gawking

If you’ve seen my newest video, you know that ancient statues of Hermaphrodite have a lot to teach us. They help us reflect on both ancient and modern perceptions of gender and bodies. Ideally, how they are displayed in museums would leverage this power to start conversations on these topics. They could enrich museumgoers’ lives considerably.

Yet no museum I know seizes this opportunity. (Perhaps you know of one! Share it in the comments below!) Instead, the statues are given little context or mediation to help viewers understand and value them. This means that they are often surrounded by tourists taking photos to show their friends, snickering about a body type they consider funny, and perhaps arousing. Large groups snapping photos of the famous “sleeping Hermaphrodite” statue in the Louvre are positively disturbing. Body shaming, bigotry, and sexual assault should be countered by museums, not encouraged. Even visitors who are deeply interested in the statue’s significance are left asking, Is this really just a funny picture? Is that all that Hermaphrodite was in antiquity too?

Museums can lead the way!

The change needs to start with museum presentation before we can expect it to spread through our society. Museums, after all, are the places for people to learn about living on this planet. Museums must stop calling the sculpture of a satyr sexually assaulting Hermaphrodite as “playful” and “titillating.” They must stop referring to Hermaphrodite as “he,” and stop exhibiting Hermaphrodite statues in places that encourage viewers to fetishize these bodies as implicitly sexualized or freakish. Instead, Hermaphrodite needs to be displayed with honesty, sensitivity, and encouragement to reflect.

Further Reading

- This excellent essay on being transgender combines a first-person perspective with a scholar’s view of ancient sculpture – and revising this view based on personal experience.

- A chapter in the book Naked Truths. Women, sexuality and gender in classical art and archaeology presents the theory that Hermaphrodite was a cult figure. See the chapter “The Only Happy Couple. Hermaphrodites and Gender” by Aileen Ajootian (preview available here).

- The book Looking at Laughter by John Clarke is a foundational work for understanding Roman humor. Beware: this may irredeemably lower your opinion of the Romans forever…

- This article admirably addresses the ongoing culture of sexual assault in art, from antiquity to the present. Unfortunately it is not freely available, but perhaps some communication with the author or press could change that: Ethics and Erotics: Receptions of an Ancient Statue of a Nymph and Satyr

- The fairly new book Gender, Identity and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture includes a chapter on Hermaphrodite. It is a fairly standard introduction to the artworks and concepts, but not quite as progressive as one might have hoped.

Have you seen Hermaphrodite artworks in museums? Share your thoughts in the comment section below!

Music Videos in Museums

A revelation has come with the new music video for the song “Dorado” by Italian rapper Mahmood. In it, the artist is shown in various locations – one of which is the “Gallery of the Kings” in the Museo Egizio in Turin. This dramatic hall is the perfect setting for Mahmood to dance and rap in part about Egypt – where his father was born. What a fabulous collaboration between modern music artist and museum! It’s beneficial to both sides. Mahmood’s video gets an evocative setting, and the museum is benefitting significantly from the press about the video. Museum director Christian Greco even gave Mahmood a tour around – another great photo op, of course, and great publicity for the museum. It shows not only the museum’s openness to allowing filming on their premises, but active embracing of the vibrant arts community.

Are other museums doing the same? So far, there haven’t been many music videos filmed in museums – but there are a few must-sees.

Perhaps most famously, The Carters (Beyoncé and Jay-Z) shot the music video for their song “Apeshit” in the Louvre. The video is a smart and visually stunning statement that certainly won over new fans for the museum.

This week the French artist Jain released a video shot in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The project was supported by YouTube and the museum itself is featured on Google Arts and Culture – indicating a new way to produce cultural content in future that reaches potentially huge audiences worldwide.

K-Pop (Korean pop) legend BTS released a music video for their song “Blood Sweat & Tears” that includes a scene in a museum – but no one has been able to find out what museum it might represent (the V&A is indeed similar but has a different floor and objects). Perhaps it was a specially constructed set.

Tim Baker released a music video for “Dance” last year that was shot in the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Canada. The video is such a beautiful sonnet to the museum that it could be made into powerful advertising – although the museum’s website sadly doesn’t seem to mention it.

In earlier history, German electronic hip hop band Deichkind filmed part of their 2014 music video for “So ‘ne Musik” in an art museum – but which one? Perhaps somewhere in Hamburg, the band’s hometown?

Finally, museums can reach new audiences through music videos created by visitors themselves. Both the Children’s Museum of the Arts New York and the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago have offered family workshops on the topic. A fun idea. Now we can hope for more music videos shot in museums in future to push this movement forward!

Do you know of other music videos shot in museums? Let us known in the comments below!

Hagia Sophia: Istanbul's Church, Mosque, Museum

The Turkish president Erdogan’s recent decision to change Hagia Sophia from a museum back into a mosque is significant. The political implications are discussed by experts elsewhere. Here, let’s take a look at the remarkable museum that Hagia Sophia was and, if all goes well, may unofficially remain. What is so significant about this place that it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is consistently one of Turkey’s most-visited attractions? What about the building makes it a museum, and what are its exhibits?

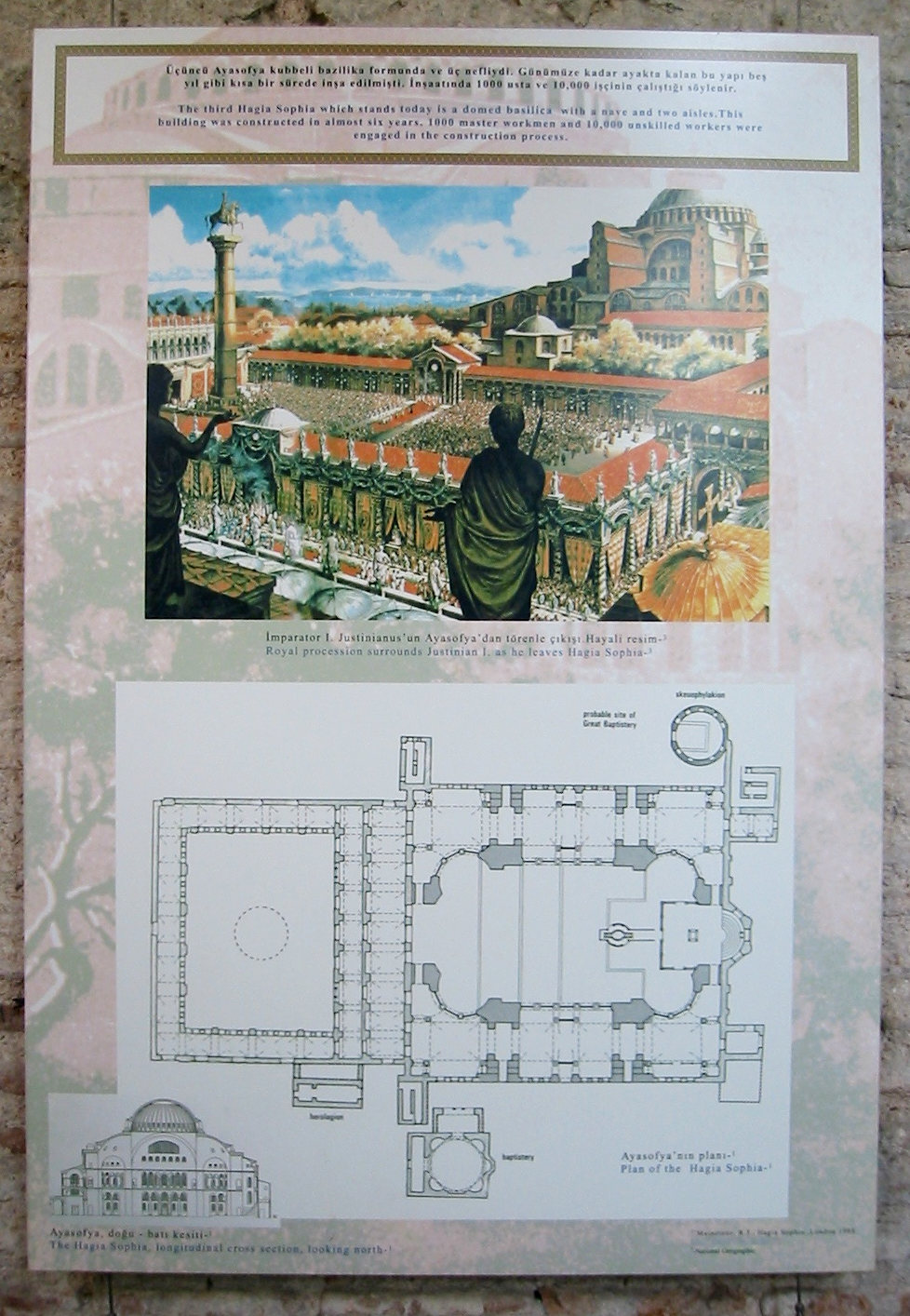

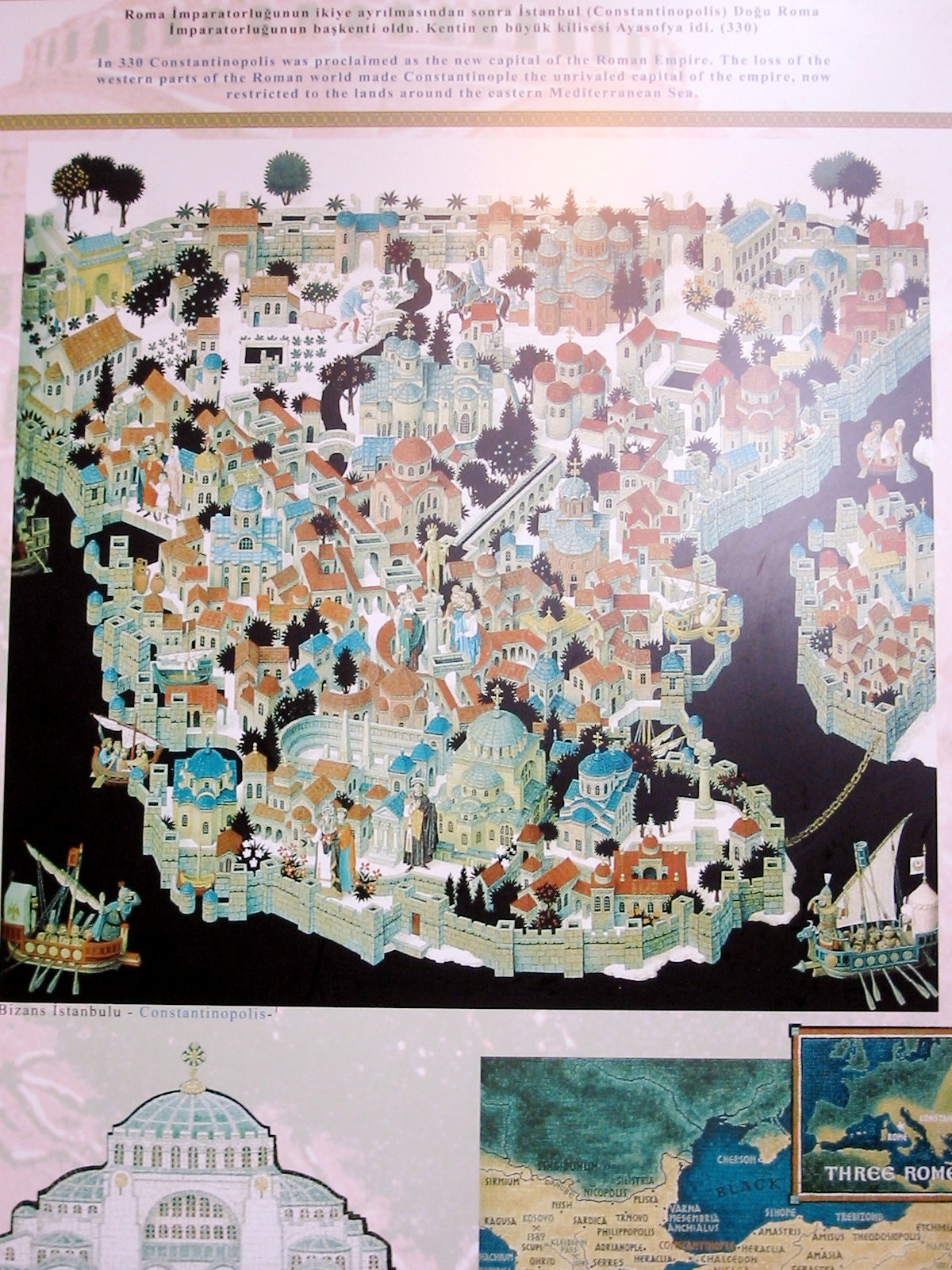

Byzantine Phase

Architecturally, Hagia Sophia is a pioneer. Its use of vaults was unprecedented when it was built in the mid-6th century AD, back when Istanbul was the Byzantine capital city Constantinople. The huge central dome balances atop a cascade of smaller domes and vaults, which support its huge weight. It was the biggest dome in the world for over 1000 years! (Surpassed only by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in the Renaissance.) In this stage of Hagia Sophia’s long life, the building served as a church – and an expression of power for Justianian, the emperor who commissioned it.

Although Istanbul’s cityscape certainly looked different in the 6th c. AD than it does now, it was every bit as cosmopolitan and urbanized. Some signs in Hagia Sophia, although scarce and old, give an impression of this. It will be interesting to see whether such signage will find a place in Hagia Sophia after it is no longer officially a museum.

Artistically too, the Byzantine building is a treasure. The marble capitals on the columns are carved in an intricate “basketweave” form, and the gilded mosaics on the walls and ceilings are breathtaking. Marble panels on the walls display the “butterfly” or “bookmatching” technique, in which two panels cut adjacently from the same block are opened outward from their common surface (like opening a book) and attached to the wall side-by-side to show off their symmetrical pattern.

In the center of the main dome is a mosaic depicting Mary holding the baby Jesus. They are surrounded by a gold surface that highlights their divinity. Both the divinity of Mary and her pose here as the bearer of God, or theotokos, reflect important developments in the early Christian church and iconography at the time. Mary was acknowledged as theotokos at one of the numerous church councils held in this period. Tragically, every single one of Hagia Sophia’s original 6th-century figural mosaics were destroyed in the Byzantine iconoclasm. The figural mosaics that exist today were made in the 10th-12th centures. This one of the theotokos is thought to reproduce the original 6th-century mosaic.

Muslim and Secular Phases

Hagia Sophia was turned from a church into a mosque when the Ottomans took over the city in 1453, and would remain so until Atatürk transformed it from a mosque into a museum in 1935. During its use as a mosque, Hagia Sophia underwent continual changes. Most notable are the four minarets that now stand at the corners of the building. Also, many of the Christian mosaics were plastered over so as not to interfere with the new Muslim function.

Smaller additions were made too, such as two massive Greek marble urns from Pergamon, added to the interior by Sultan Murad III in the 16th century. Importantly, many of the Christian features of the building were preserved under their layer of plaster so that they could be revealed when the building became a museum in 1935. Thus Hagia Sophia was able to display the many layers of history she had already survived.

It is clear from this long and turbulent history that Hagia Sophia can only be a monument to history if it is preserved intact. Thankfully, the Byzantine iconoclasm was the worst destruction suffered by the building so far. The current plan is to to use Hagia Sophia as a mosque – covering the images during services – but still to allow all visitors free access outside of services. If this is maintained, and if the integrity of the building and its history is cared for, Hagia Sophia will be able to serve as an unofficial museum for a long time yet.

Diversity and Community Inclusion in Museums

My newest video focuses on diversity in the ancient art of Berlin’s Altes Museum. It offers a perfect chance to collect some of the wonderful resources that museums are putting out to reach their diverse audiences, and to draw attention to this pressing issue. Here is a brief collection of some of my favorites. Please comment below with further ideas!

- The Myseum of Toronto is a paragon of Community Responsive Programming. This museum doesn’t even have a building – it consists purely of initiatives that go out into the community to make a difference!

- I love the idea of a Social Justice Curator. Jasmine Wahi at the Bronx Museum of the Arts is making use of this position by putting on exhibitions and much more about pressing social issues. One statement in her interview for ArtNews struck me in particular: “The paintings Khari [Turner, artist] showed me were saturated with color, and evoked a sense of jubilation. Moments of joy are so important right now: social justice in art is not just about illustrating injustice. It’s also about fighting for our right to be joyful.” Check out the Bronx Museum’s list of social justice resources here.

- The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow put untold thought, passion, and resources into reaching their community during the pandemic. They particularly built up their programming for autistic and hearing-impaired visitors. Inspiring not just for our vision of museums, but of humanity!

The video “White at the Museum” by the Lucas Brothers (shown on Full Frontal with Samantha Bee) is a highly entertaining look at the very serious subject of whitewashing Greek and Roman art. It is exactly the right dose of academic learning mixed with social responsibility and, yes, humor.

Have you discovered other ways that museums are using to prioritize diversity and community inclusion? Let us know below in the comments!

Roosevelt, The NewOnes, and other Statues fronting Museums

With numerous commemorative statues being toppled these days, those in front of museums have become a focus like never before. The American Museum of Natural History decided to remove the statue of Theodore Roosevelt from in front of the building because of protests (ongoing for years) about the way it depicts two figures, an African man and a Native man, behind the president. The museum had already created an exhibition about the statue and its controversy but decided to move it just last week, in light of the most recent protests.

Meantime, The Metropolitan Museum decided in the fall of 2019 to erect statues in the niches of the Fifth Avenue building’s facade – which had stood empty since construction ended in 1902. Obviously (or is it obvious?), the commission had to be contemporary in avoiding traditional hierarchies and histories, presenting instead a worldly vision befitting a cultural institution in the 21st century. Kenyan-American artist Wangechi Mutu met the challenge with grace and strength. She created four magnificent bronze statues whose monumentality suits the facade, but whose very modern forms ask us to think about what we expect from monumental statues. This is a brilliant way for a museum to engage with ongoing discussions in a constructive way.

Both the destructive and constructive acts around statues – in front of museums, inside museums, and unrelated to museums – prompt us to reflect on the place of commemorative statues in our societies today. Do historical figures serve a purpose in this memorialized context? Do personifications or symbolic figures? (Like the Lion Fighter in front of Berlin’s Altes Museum, shown at right.) Artworks have a powerful effect on their human “interactors,” as current events attest. Museums are far from neutral spaces; to the contrary, they make decisions about what to display and how to display it. The statues in front of them are just the tip of the iceberg.

UPDATED! How Museums Are Fighting Racism

UPDATE June 29, 2020: The original post from June 17, 2020 has been updated to reflect new and newfound resources on the topic, which have been added at the bottom.

Museums are responding to the #BlackLivesMatter movement, offering new materials to teach and promote anti-racism. Of course, it is also important to consider how much museums do – not just the resources they offer – to combat racism, such as offering paid internships so that not only financially well-off people can afford them. But making learning resources publically available is another huge and necessary step, central to the museum’s mission as a public institution, which is worth taking a look at. Here are a few case studies that I find particularly heartening.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture set up an entire portal called “Talking About Race” with a wonderfully accessible set of materials (press release here). This portal was already in the works but the publishing date was moved up in light of current events. Here you can explore themes, or select your motivation for visiting the site – I’m a parent / I want to be an advocate / I’m a teacher. There is a beautiful mixture of texts from the historical to the poetic to the pedagogical, alongside videos and photos; it really encourages you to dive in, whatever your favorite mode of engaging is.

The Metropolitan Museum addresses racism in its offerings in other ways. It has posted a letter from the leadership on its homepage, but perhaps more accessible and interesting to most visitors are the other resources. Such as an interview with two Senegalese fellows who worked on the exhibition Sahel: Art and Empire on the Shores of the Sahara, which opened before the pandemic closures. In this way, the museum is not announcing an anti-racist agenda in so many words, but is supporting one through the exhibition and, most of all, through the collaboration with Senegalese specialists.

Another tack is taken by the British Museum, which invited former trustee Bonnie Greer to write about trauma and reclamation on the museum blog. The playwright’s words are powerful and personal. Of museums in particular she writes: “Museums hold arcs. They hold them in the people who work there, in the objects, in the scholarship, and in the building itself. / Reclamation becomes an arc in which truth can be discovered. And perhaps, if we are all lucky, trauma healed.” She envisions museums as containing arcs, precious containers of truth or scripture – but these themselves are inside the people, objects, and research, as well as the building. You might be able to say this about other buildings too, but I think that museums are especially suited to this idea because of their mission of teaching.

The Albertinum in Dresden has organized an exhibition with the title One Million Roses for Angela Davis, dedicatd to the black rights activist’s time in East Germany. Due to open in October, this exhibition is a strong statement against the continuing racism in the region around Dresden. In this way it resembles the fantastic 2018 exhibition in Dresden’s Hygiene Museum, Racism. The Invention of Human Races – one of the best exhibitions I’ve seen, not least for its powerful intervention in a region that sorely needs it.

Further initiatives have come to my attention since the original post on June 19, 2020:

- A museum of contemporary art in Rotterdam, Netherlands has decided to choose a new name in order to distance itself from the colonial figure in its current name, The Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art. Although the museum’s name comes from the name of the street that it is on, Witte de Withstraat (straat=street), the museum recognized in 2017 during a program on decolonization that its name should be changed. Recent events have now prompted faster action, such that the museum will change the name this year and in the meantime is calling itself the “Formerly Known as Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art.” The public is encouraged to weigh in at the online forum and survey!

- A virtual exhibition in honor of George Floyd has been created by Karim Farishta and turned into a full-fledged virtual space that even schools are now showing interest in using. Under the hashtag #ArtforJustic, Farishta solicited artworks that now are displayed in the exhibition. You can visit it here.

Do you know of other museums rethinking their materials and structures to keep pace with the current changes? Let us know in the comments below – we’d love to hear from you!